Set Yourself Free

Whatever level you compete at, experiencing intermittent radio interference is a sure way to ruin your race day

Making a mistake in your fastest qualifying run might be annoying; being bundled off the circuit by a throttle-crazed racer even more so. But for a really annoying racing experience, there is one clear winner – radio interference. Suffer from the dreaded glitches and your entire race meeting can be ruined as you remain in control of the car for some laps and periodically lose control on others. Sometimes the interference only occurs at specific parts of the race circuit and often only at really opportune moments, such as when dicing for position or being lapped by the race leader. But while the glitches themselves might be annoying, the ensuing search for the root cause can be both frustrating and time consuming, with a combination of systematic elimination and “trial and error†needed to discover a cure.

A radio “glitch†is clearly different to having someone switch-on a transmitter using the same frequency as your own. If this happens, you soon know about it since your car rapidly becomes completely uncontrollable. Instead, a “glitch†is typically defined as an unwanted event that occurs over a short period of time; an event that can’t be easily repeated. In a radio-control car that means an errant electronic signal occurs that causes the radio equipment to respond, a signal that was definitely not generated by the driver’s own movements on the transmitter controls. The good news is that there is a genuine reason why most glitches occur. The bad news is that it can take some time to find it. So to help in that process, here is our guide to ten common causes of radio glitches.

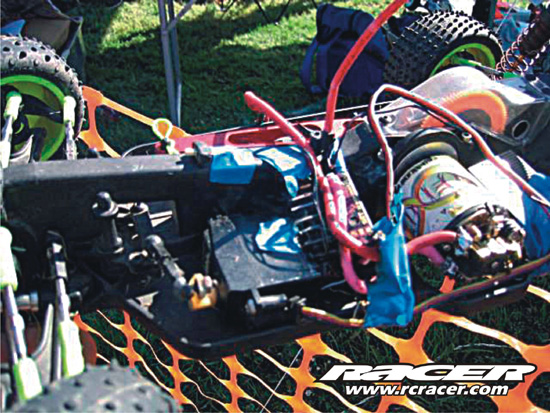

1. Unreliable Connections

Intermittent electrical contract can generate power spikes and cause glitches, and the main culprits are usually dodgy connectors or poor solder joints. Finding the exact problem area can prove difficult, not least because what may appear to be a reliable connection while the car is stationary may prove to be less so when it is hurtling round the racetrack. Dry solder joints are the first obvious targets to look for. Check all leads to ensure the soldered connections are firm and are not liable to break apart when the wire is given a short tug. Then check the connectors themselves to ensure they fit together securely and do not shake about. The plugs into the receiver are prime candidates to check, particularly when mixing the receiver and servos from different manufacturers.

2. Receiver Aerial Route

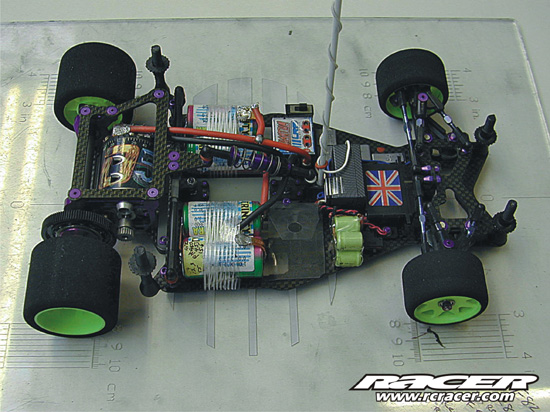

The way the aerial has been routed in the car will affect its sensitivity. The intent should always be for the aerial to go from the receiver and up and out of the car as quickly as possible, keeping it well away from the conductive metal or carbon-fibre found on the chassis. If the receiver aerial is too long, it should never, ever be cut. For each make of receiver, the length of the aerial is accurately calculated, and for maximum sensitivity it must remain at exactly that size. Since most aerials are longer than the accompanying aerial tubes, most drivers make small neat coils of the remaining wire on top of the receiver. Others go one better and use an internal antenna loom that ensures the aerial never loops over itself. Moving the receiver around in the car or mounting it on its side are other tricks that can help to ensure a reliable radio signal is received.

3. Lead Length

Keeping the lengths of radio leads to a minimum can eliminate the need to loop and tie them together, and allows them to be more neatly routed in the car. Most top racers trim and re-solder the servo and speed-controller leads so that there is just enough slack to allow the removal of the items without straining the connections. With older equipment for which the warranty has expired, an even neater rewiring job can be performed by dismantling the unit and re-soldering the wire at the circuit board end. Do not attempt to change the lengths of radio leads unless you are proficient at soldering though. You might eliminate the glitches caused by unnecessarily long and looped leads, but introduce glitches caused by unreliable connections.

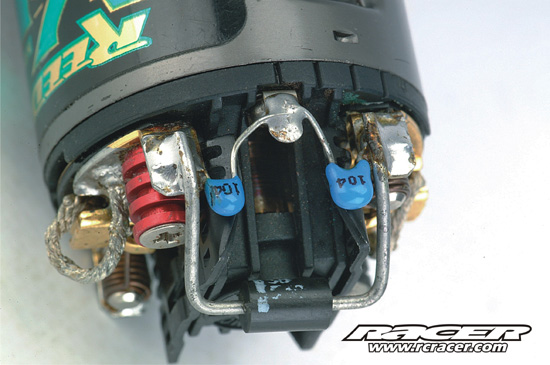

4. Motor Arcing

In an electric car, many of the unwanted radio frequencies are generated by the motor. In a brushed motor, as the motor brushes bounce up and down on the rotating commutator, they generate radio frequencies, which can affect the

receiver. To suppress these signals, small ceramic capacitors are soldered to the end-bell of the motor. On some modified motors, these come pre-installed; on others they will be included in the packet and require soldering into position. Use a hot soldering iron to do this and keep the capacitor legs as short as possible to ensure they do not catch on the chassis when the motor is installed. Whenever you remove the motor from the car, check the capacitors to ensure they remain firmly soldered in place. A dry solder joint on one of the legs can be enough to give the car major radio interference. Many high frequency speed-controllers also require a Schottky diode to be fitted, which further isolates high voltage spikes.

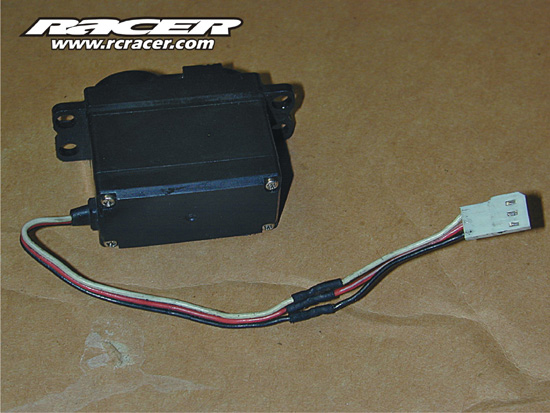

5. Receiver Voltage

All receivers only operate correctly when they receive an input voltage in the manufacturer specified range. If the input voltage to the receiver gets too low, then glitches can occur. When running your car off an external receiver battery pack, the cells must therefore be fresh or recently charged. In an electric car where the power comes from the main battery pack itself, the appropriate elimination circuitry must be used. Modern electronic speed-controllers have such voltage regulators built in and will ensure the radio equipment is always given priority over the supply of power to the motor.

6. Transmitter Problems

It should go without saying that the transmitter itself should be in perfect working order and complete with a charged battery. Checking the voltage on the meter provides a quick way to verify this. To find out whether the radio equipment itself is the cause of your “glitchesâ€, replace the transmitter and receiver with the combination from one of your other cars. Alternatively, borrow a unit from another driver. If the car does not glitch with the new equipment you can be pretty sure the original combination is at fault. It can be repaired by returning it to the authorised distributor, together with a detailed letter explaining the exact problem. Make sure you get a quote for the required work first so that there are no financial surprises.

7. Frequency Choice

While occasionally caused by a damaged crystal, most frequency related glitches occur when running frequencies that are very close to the others in use in the race. A slightly out of tune transmitter, running on a frequency close to your own, can cause signals that get picked up by your own car. For that reason, most race directors try to leave a “double gap†of frequencies in each race, ensuring a good spread across the available range. They may be less likely to do this for the finals though, so check the listing when it is posted and ask to change frequency if you end up immediately adjacent to another. Frequency monitors are available that can detect when a transmitter is giving out a rogue signal and these are used in major race meetings when a driver makes a call for radio interference before the start of a race.

8. Rostrum Position

Moving positions on the rostrum might sound like a dubious cure, but it is amazing how many times this can work. If the glitch only occurs at one particular point on the race circuit, only when stood next to a particular driver or only when driving under the transmitter aerials of other drivers, then changing positions can provide a simple cure. There is usually a more logical reason why your receiver is proving to be particularly sensitive to the signals generated by other transmitters, but this is one of the few cures you can attempt during a race. The other is to consciously change the angle at which you are holding the transmitter aerial, ensuring it points upwards rather than down into the ground.

9. Other Drivers

Occasionally it may not be your car or radio equipment that is at fault. Some drivers have been known to boost the power output of their transmitter by adding extra cells, a practice that is specifically outlawed by the British Radio Car Association (BRCA). The BRCA 1:10 off-road rules allow the Race Director to randomly ask competitors to open their transmitter case to prove they are not cheating in this way. Some drivers have been caught running illegal frequencies outside of the approved range too; again, if the Race Director detects such activity, the punishment is usually instant disqualification.

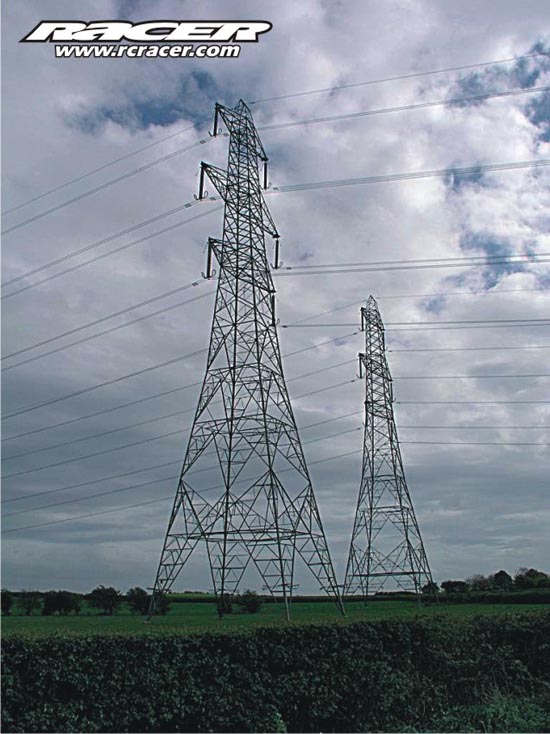

10. External Radio Signals

If you are racing near power lines or a radio or television transmitter, there is a chance that the other radio signals in the area may be so strong that the receiver is not able to reject them. We have even seen instances where the public address system used by the race commentator has caused cars to glitch. Thankfully, outside interference of this kind is relatively rare and can sometimes be cured by switching off the offending item. In the worst case, you will need to change the location of your race, moving to an area where the only signals generated are those from the radio-control transmitters.

Avoiding Interference

Curing interference can be difficult, but there are now at least two excellent ways to help avoid getting it in the first place. The first method has been around for years; the second is new and potentially very exciting.

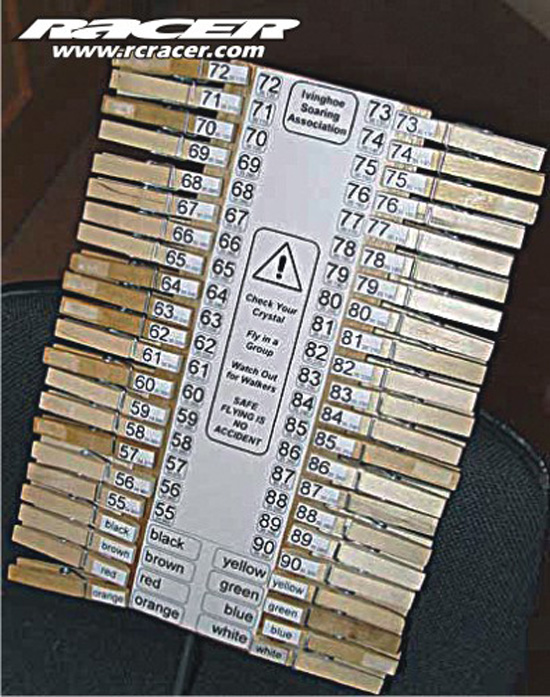

Use a Peg Board

The simplest solution to avoid two people attempting to use the same frequency at the same time is the “peg boardâ€. Variations of this are seen at most clubs across the country. The principle is easy. Before you switch on your transmitter, you must first collect the wooden clothes peg that corresponds to your frequency from a board next to the drivers’ rostrum. You clip the peg on your transmitter and only then can you switch it on. Once you have finished racing, you switch everything off and then place the peg back on the board. If a driver goes to collect a peg and it isn’t there, it indicates that someone else is already using that frequency. Therefore the driver must either wait for the current user to finish, or should change to another frequency. Of course, it requires discipline from all of the drivers for this system to work well, but it has been used at many, many meetings over the years with considerable success.

Use Spektrum

What if you took the concept of the peg-board, and made a transmitter and receiver that worked in the same way? Wouldn’t it be great if you could simply switch on your transmitter and it would then automatically scan all of the available frequencies and lock onto one that was available? Then when you switched your transmitter off, the frequency would be automatically released for someone else to use. In fact, with a system like this, the days of suffering radio interference caused by a driver switching on a transmitter using the same frequency as you would be over. In fact, if everyone used it, the pegboard would become redundant too!

Amazingly, such systems became a reality at the end of 2005 when approval was granted to use radio control systems based on “Direct Sequencing Spread Spectrum†technology, as pioneered with the Spektrum radio system. This technical marvel can search all 79 allocated frequencies in the 2.4GHz band and then lock onto one that is free. Interference protection is also improved through the use of a unique identification key. When the receiver detects an incoming signal, it first checks the identification key to confirm the signal came from your transmitter. If it didn’t, the signal is simply ignored. Another bonus is that the 2.4GHz band is a long way away from other frequencies generated inside the car, such as those caused by arcing motors, vibrating metal parts, and speed controllers. These frequencies typically occur at less than 300MHz and have to be suppressed when using a conventional radio system by fitted appropriate capacitors and diodes.

And if that still doesn’t sound good enough, the Spektrum units are the fastest responding radio systems around, the transmitter uses a lot less power than normal, and the very short receiver aerial can actually remain inside the bodyshell of the car. What’s more, the receiver is even capable of transmitting signals from the car back to the pit area, opening up a wealth of future possibilities for on-board telemetry systems. It’s no wonder that many drivers have started converting their radio systems over to the 2.4GHz-operating band!